I woke up this morning to news of Nvidia’s latest impressive stock surge – yet again confounding its critics and the doom-mongers convinced the AI bubble is moments from bursting.

It doesn’t surprise me. AI’s galloping pace is unmistakable, and its technologies are now running wild through the day-to-day interactions and transactions of businesses and organisations. Supply chains, customer service, drug discovery, industrial design, logistics – AI is under the bonnet of so many things we rely on.

Perhaps more striking is the shift and uptake of AI not by organisations, but by individuals. An ever-growing majority of the world’s population now uses AI in some form. To keep things in perspective, here’s the rough scale (pulled up using ChatGPT, naturally): there are 5.5-6 billion people online; roughly the same number using smartphones; and close to a billion already interacting with AI tools – often without even knowing it.

Whatever definitions countries choose when reporting AI usage, it’s getting harder to maintain the fantasy that AI is niche or peripheral. It’s mainstream.

And, although we talk about AI as if it has “just arrived,” it’s been with us for far longer.

The field traces back to the 1940s, when Alan Turing first imagined machines that could think. I re-watched The Imitation Game (the movie about him) on a flight this summer, and was far more absorbed in the storyline than I remembered being when I first watched it ten years ago. Back then, AI felt like a curiosity, whereas now it feels like the backdrop of our lives.

From Turing’s wartime code-breaking machines, the formal study of AI began in 1956, then wandered along for decades before suddenly accelerating in the 2010s with deep learning and the rise of powerful computing. What looks like a “sudden revolution” today is really just the latest chapter in an 80-year experiment.

ChatGPT arrived only three years ago. Its exponential uptake (1 million users in five days, 100 million in two months) made it one of the fastest-adopted technologies in human history. Generative AI went mainstream so quickly that many formed opinions on it only after it was already shaping our routines.

I use AI a lot in my work, and try to treat it as something that expands my thinking rather than replaces it. It’s easy, though, to feel the seduction of outsourcing increasing amounts of the boring brain stuff we deal with to a machine.

When I heard friends first using it to write emails and text messages, I remember thinking: this surely won’t last. And yet here we are. AI now writes, translates, analyses, drafts, refines, designs, and increasingly does it frighteningly well.

If everything we have to do becomes effortless, what happens to the mental muscle we use when things are hard? What happens to reasoning and curiosity? What about our memories and about our accountability?

Earlier this month, the New York Times posted an article called How A.I. and Social Media Contribute to ‘Brain Rot’. The Harvard Gazette ran a similar piece last week, and The Guardian and MSN picked up coverage of Nataliya Kosmyna, an MIT Media Lab scientist whose recent study of Chat GPT made waves.

All raise similar worries – some calling it “brain rot,” others “cognitive atrophy.” Kosmyna and her fellow researchers found that users who leaned on AI for writing tasks remembered less of what they had written, and showed diminished activity in brain networks tied to attention and reasoning. One educator interviewed described AI as “a brilliant assistant, but a terrible replacement for struggle.”

This feels about right.

And yet, the same research argues that, used reflectively, AI can make us more creative, more productive, and even more curious. The key distinction is, perhaps, intention: it’s not the presence of AI that dulls us, it’s the absence of our own engagement.

I’d noticed my own habits shifting in that direction, and so took a step back. In doing so I felt myself pushed in the opposite direction: towards more reading, more handwriting, and more analogue time.

I wrote about this over on Substack earlier this year, Rewinding With a Bic Pen, because I felt that slowing down into the older rhythms of writing was helping me stretch my attention, rather than scatter it.

However, at the same time, I’d say that AI has made me much more efficient in my work – researching, planning, synthesising ideas, prepping workshops, threading insights into reports. Using AI has meant I can carve out more time, not less, for other things that matter. It’s a perfect conundrum if you ask me: not classically good or bad.

My daughter’s school is, understandably, trying to protect students from AI – or at least slow it down – and I don’t feel nervous about their classroom experiences being compromised. But the truth is unavoidable: their world will be steeped in AI whether we delay it or not. The question isn’t how long we can hold it back – it’s how well we can teach them to use it with care and curiosity.

I definitely crave simpler times, simpler tools, simpler choices. I find myself saying this more and more. Although nothing in the rulebook says we can’t keep hold of the simple things while still letting technology widen the possibilities around us. The analogue and the digital can coexist.

In the end, I’m personally on board with AI. I see its risks, and I also see the enormous potential for good (plus the way it has already nudged me back into more deliberate, thoughtful habits.)

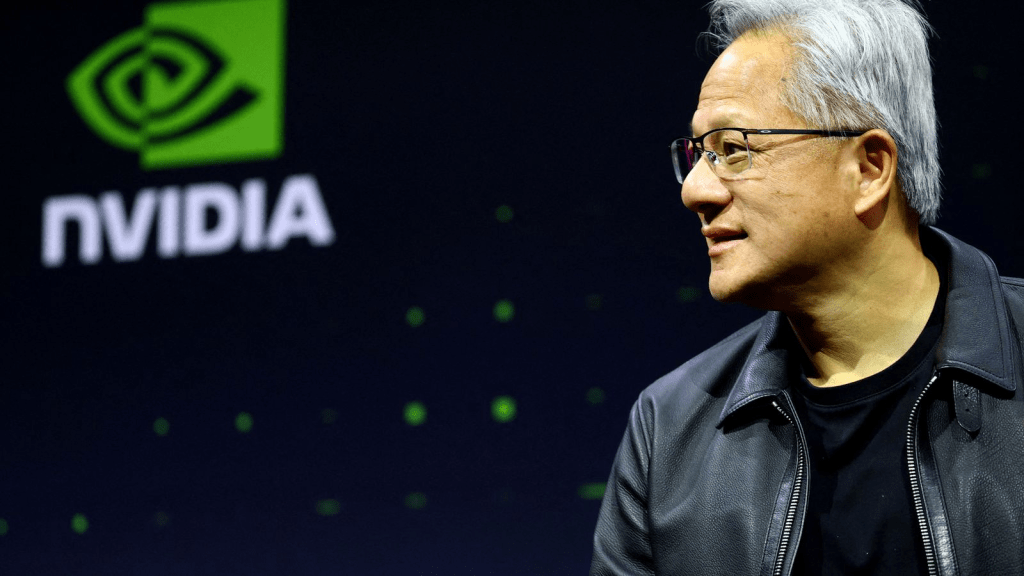

It’s hard to sum things up. Particularly when I’m nowhere near understanding or predicting AI’s evolution, nor the financial ripples a company like Nvidia is casting across global markets. The numbers are too big for me to take seriously. When I see speculation about Elon Musk edging closer to “trillionaire” status, or Jensen Huang’s net worth doing somersaults, I tend to scroll past it and simply go off to make myself a strong cup of tea.

In the end, AI is a mirror that reflects our cravings as much as our creativity. It shows our hunger for ease, our impatience, and our distractibility – in those moments, we look like one vast Pavlov’s-dog experiment, staring up, waiting for the next treat. But it also reflects our imagination and our ability to build astonishing things.

It holds both truths at once.

And so, arguably, the real question isn’t whether AI will be good or bad, but who we choose to become while using it.