I read two things last week, coincidentally connected.

The first was a report from CARE International, offering insights about the impact COVID-19 has had on the local community groups that CARE has been seeking to support for decades.

I commend this report to anyone with an interest in the topic of international development. The analysis is rigorous, yet the recommendations are simple. The tone is calm, but unsettling, given the evidence being shared, which points not to the successes of the international development community, but instead underscores its failures.

It cites how impactful the pandemic has been, in terms of increasing, rather than decreasing, gender inequalities.

It also proposes that far too much potential progress in development is “held back by the deeply colonial approaches” still adopted by global development organisations, including CARE themselves.

Sifting through social media feeds, I then stumbled upon this quote from the novelist and cultural critic, James Baldwin:

“The entire purpose of society is to create a bulwark against the inner and the outer chaos, in order to make life bearable and to keep the human race alive. And it is absolutely inevitable that when a tradition has been evolved, whatever the tradition is, the people, in general, will suppose it to have existed from before the beginning of time and will be most unwilling and indeed unable to conceive of any changes in it. They do not know how they will live without those traditions that have given them their identity. Their reaction, when it is suggested that they can or that they must, is panic… And a higher level of consciousness among the people is the only hope we have, now or in the future, of minimizing human damage.”

Drawing these two “things” together (CARE’s report and Baldwin’s musings) doesn’t take a considerable amount of effort: the traditions to which Baldwin refers, are part of the very reason that international development has failed. The traditions that dictate the colonial influences over how aid has been invested, coupled with the traditions which set the social and cultural constructs that exist on the side of the recipients of that aid, create a perfect storm of incompatibility.

For sure, there are examples of success, and I have spent time on these pages promoting them.

Unfortunately, these are overshadowed by examples of failure, and worse: examples of repeatedly making the same mistakes over and again.

In 1948, the United States committed to the rehabilitation of Western Europe, kicking off the “Marshall Plan” as an investment to help countries after the War.

Many of the recipient countries of the Marshall Plan – Britain, France, Netherlands, Belgium, West Germany and Norway – had, themselves, previous experience of providing aid to countries years before.

Foreign assistance, as a concept, had been around since the 18th century. However, since that time, the majority of the assistance given was from countries such as Britain and France, and predominantly to their respective colonies.

To recap, hastily, on how development has evolved since 1948, organisations (such as CARE International) have invested significant time and energy trying to understand how to most appropriately and effectively assist those “living in poverty”.

Those last three words are in speech marks, because defining who beneficiaries actually are has, itself, been a 75-year exercise.

The World Bank annually grade country demographics and, historically, many aid organisations and government donors use this guidance to allocate funds. Which is why more recently South American countries and now South East Asian ones, are receiving less “aid” due to how they have slowly climbed the World Bank rankings, moving from “low income” to “medium income” economies.

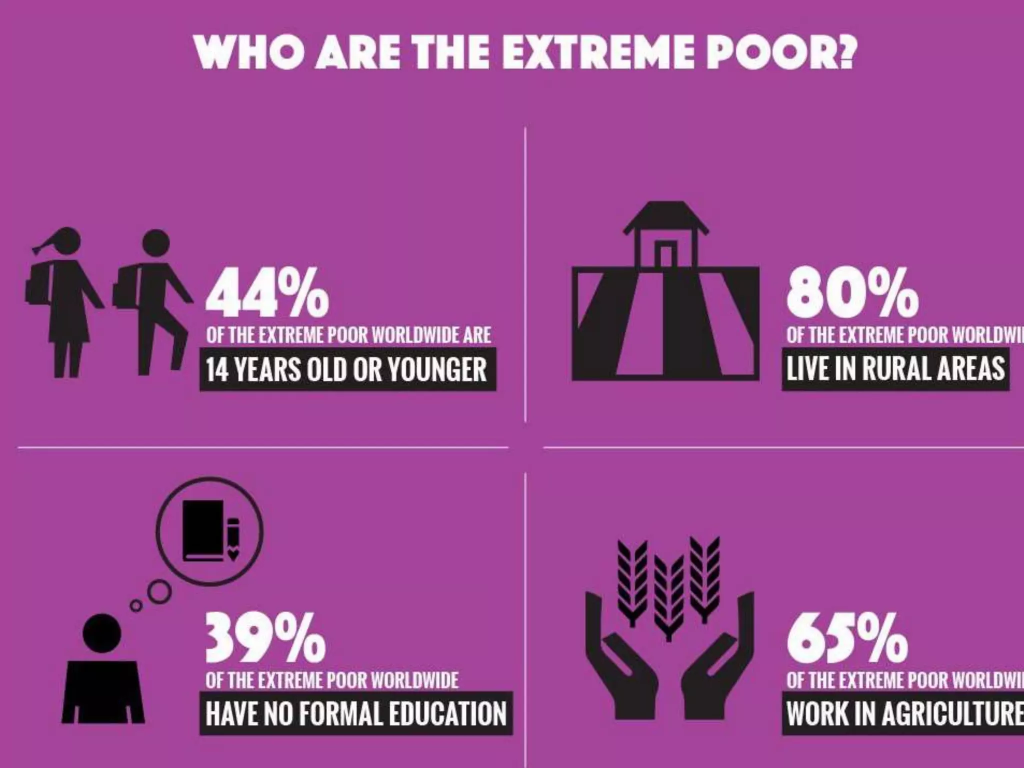

Using economic indicators such as these, some development agencies have prioritised the “extreme poor” as a target group for receiving aid.

Whilst others have nuanced their criteria for “poverty” and zoomed in on defining groups of people based on how “vulnerable” or “marginalised” they might be, which then takes into account criteria beyond income.

Over time, and as the international development industry has expanded, more types of people in need are included, in some way, by some organisation, or movement.

In any case, whilst they have been undertaking their deep dive analyses, and designing their ever-complex programmes, these organisations have encountered a slew of cultural and social normative behaviours (again, Baldwin’s ‘traditions’ – to which each community they are assisting is bound and, from which each community is so heavily defined.

For CARE, the gendered aspects of such cultural traditions – whereby men typically dominate decision making and hold the majority of power over women (at home, in the workplace, and in public spaces) – has become the lynchpin around which all of CARE’s efforts have been inspired.

For others, UNICEF or Plan International, for example, their research and development has anchored itself to the challenges that children or young people, respectively, face in society.

As many commentators have cited, the evolution of “aid” over the last 200 years has charted a meandering course, undergoing regular modifications.

Take the topic of financing, for example.

Many nations, and large development organisations, have explored what might be the most efficient financial instruments they can deploy: Government-to-Government loans; microfinance programmes; economic stimulus packages; public-private funded initiatives, designed to strengthen economies and improve societal issues.

Each of these examples, come with their own success stories however, without exception, each encountered this same obstacle of tradition on both sides of the equation: the traditional norms set by those investing funds and resources into development, and the traditional norms played out by those receiving the financial “help”.

Given these constraints, it is simply not clear, even today, what types of interventions are best and how these should be delivered.

Is it more appropriate, for example, to stimulate economic growth for a country or, instead, better to understand upfront what is needed by those in that country who are struggling financially and who are excluded from formal systems (ie they lack access to bank accounts, internet, markets, education, etc) and to design an intervention that addresses that need?

Both of these approaches have been tried and tested and, in some cases, combined. However, again, traditional norms create obstacles along the way.

For example, direct budgetary support (a financial transaction between Governments) was, for a while, a popular choice of many richer nations to financially support poorer ones. Yet, this type of support could be all too often undermined by recipient Governments not properly distributing the funds through public services. Instead, many would funnel disproportionate amounts into other areas, such as to the bank accounts of Government officials.

And, when it comes to implementing the second approach (ie answering the “needs” question) this, too, can be compromised by the nature of who makes decisions in society, writ large.

Not exclusively, but typically, all such development-based transactions, and development-based relationships in the past were led by men.

The result of which is that less consideration, over seven decades of international development, has categorically been attributed to those societal issues that would have been selected by women. Women simply haven’t had the opportunity to have an equal voice in conversations about international development in that time. Not in the initial orchestration of The Marshall Plan, nor in the decisions with, and within, communities in terms of where and how the resources should be utilised.

Photo credit: Tim Bishop

It was CARE who established the first ever Village Savings and Loans Association (VSLA) in Niger in 1991, a mechanism for women to save and loan money with one another.

This, in turn, inspired the scale up of VSLA platforms around the world, adopted by other organisations too, encouraging women to have a voice inside of communities, and ultimately enabling women to speak out and influence local structures and systems.

VSLAs are one example of how this acutely gendered dynamic and imbalance is shifting. Unfortunately, the pace of change is slow.

Take the issue of unpaid care. This remains a pertinent topic even in the most “progressive” of societies. In the world of business, equal pay and worker benefits are also not yet level for all employees. For many nations, their politicians and leaders have been, and in many cases remain to be, male dominated. As of 2021, only 1 in 5 ministerial positions globally were held by women and, even today, just 17 countries have a woman Head of State, and 19 countries have a woman Head of Government.

These stark ratios are reflected, too, at the local level of the majority of countries – in the political and public spaces of local authorities and community leaders, in small to medium enterprises and local businesses. The patterns are similar, the outcomes the same.

And, whilst today’s inter-connected world has increasingly called out these gender imbalances, in a way that simply wasn’t viable even 20 years ago, Baldwin’s intuition when he writes “They do not know how they will live without those traditions that have given them their identity” rings true.

Just as traditional norms hold back gender equality, so too do they stifle advancements made around other forms of inequality.

More than ever, we have been made aware of the economic inequalities of the world – the “1%” phenomenon.

Every country maintains its own version of this and, globally, it would seem that the ratios of the ‘haves’ and the ‘have nots’ become ever more extreme with each annual set of data released.

According to last year’s World Inequality Report, “Global wealth inequalities are even more pronounced than income inequalities. The poorest half of the global population barely owns any wealth at all, possessing just 2% of the total. In contrast, the richest 10% of the global population own 76% of all wealth.”

Armed with such data, it is hard not to side with those campaigning for change. Be that from an accountability perspective, lobbying for more responsible policies and practices adopted by business and by government institutions. Or be it from a more ethical perspective, targeting individual behaviours.

Both make sense, yet both have their limitations when it comes to just how much ground individuals, corporations, or governments, are prepared to concede at their own expense.

***********************************************************

With power comes responsibility, and all too often that responsibility lies in the shadow of a tradition that is extremely hard to change.

Whether you set your sights on tackling inequality, poverty, vulnerability, marginalisation, gender equity, disability, child rights, or other such societal issues, I would argue that Baldwin’s plea for a “higher level of consciousness” remains, simultaneously, a sobering as well as a viable salvation, when redressing some sort of balance in the world.

Although I was tempted to end this post conceding that Baldwin’s call to action might never be fulfilled, instead I would suggest that the subject of ‘consciousness’ gains more traction with each generation.

What if we kept a higher level of consciousness close to heart, and nurtured that sense of what it can mean each day? What if we tried to imbue Baldwin’s words and sentiment into as many interactions, thoughts, exchanges and relationships that we could accommodate?

Do this, and perhaps there may yet come a time where our connectivity with one another sets in train a new sense of what tradition is, what it stands for, and what new outcomes it might reveal.