Trends have a habit of swinging like pendulums. First something is ignored, then it becomes important, then it becomes very important. Eventually it becomes so important that everyone talks about it endlessly – until the backlash arrives and people pretend they were never quite that enthusiastic about it in the first place.

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) went through this earlier in the 21st century, swinging through a melee of definitions and frameworks for quite some time. The moment that started to shift CSR into a new paradigm came in 2011, when the Harvard Business Review published Creating Shared Value by Michael E. Porter and Mark R. Kramer. Their argument was simple but powerful: companies should stop thinking about social impact as philanthropy and start seeing it as strategy.

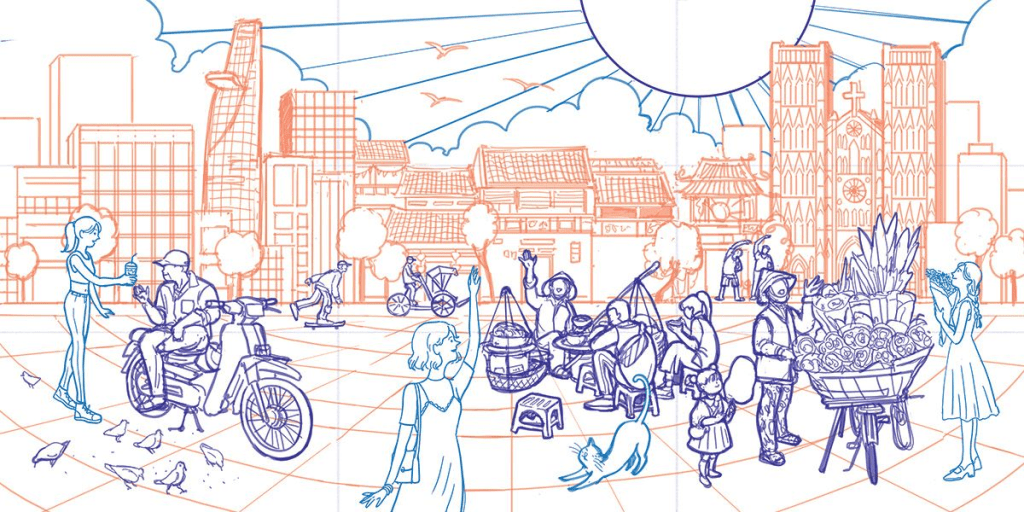

In hindsight, I think this marked the moment when social responsibility stopped being a side activity and started edging toward the core of business strategy. I remember 2011 particularly well. It was the year I moved to Saigon and began attending – and occasionally speaking at – CSR conferences in Bangkok and Singapore. Suddenly everyone was talking about CSR being all about partnerships, collaborations, and how business could create both profit and social value at the same time.

CSR over here in Asia was cresting its wave back then, associated as it was with Porter and Kramer’s theory and less with the previous bolted on, and rather tokenistic, CSR practices. Much of the old, PR-centric ways began to lose their shine, finding themselves repeatedly accused of greenwashing.

While CSR still exists today as a function in business, I’d say those companies using it have nuanced how they describe it so that it comes across much more as a business model, rather than as an add-on. Which is what it was always intended to be.

However, a fair number of years before COVID-19 was to strike, CSR was nudged aside by ‘Sustainability’. Riding into town like a gun-slinging John Wayne, and charging through the swing doors of every industry, blasting away the many offshoots of CSR that had come before it, Sustainability was the word of the moment.

Sustainability earned its spurs pretty quickly and still enjoys the spoils of a period that spans at least the last decade. Many larger corporations will tell you they’ve had sustainability strategies for longer that that, however it’s hard to always find compelling evidence for this.

As all-consuming concepts go, Sustainability covers a lot, and I don’t see it going anywhere for a while. More recently, it has been accompanied by its trusty side-kick: DEI (Diversity, Equity and Inclusion) galloping from pillar to post, infiltrating HR departments and budgets with training modules and policies.

To be clear, the business cases for all of these ideas have been well made. DEI has one – linked to ethics as well as business performance – and, as the constant digital transformation of our lives further advances, the blanket understanding of these concepts has gradually grown to a healthy level.

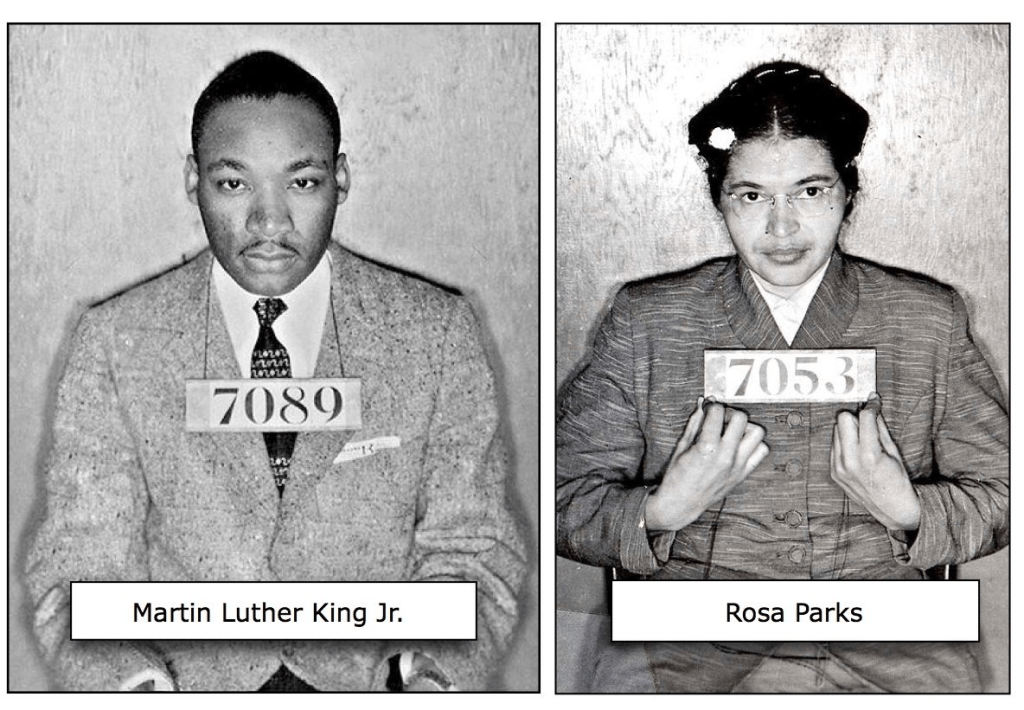

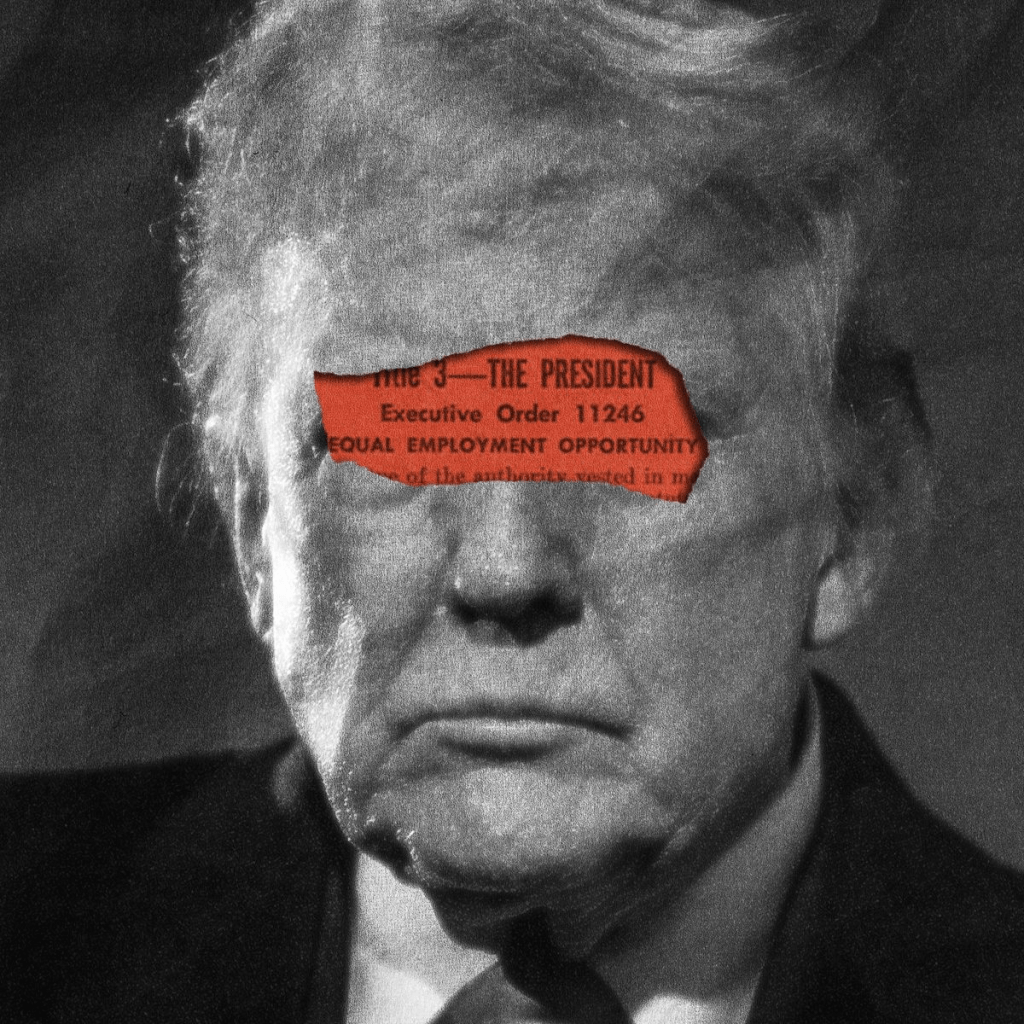

For a while there, particularly in the United States, the corporate world embraced DEI with extraordinary zeal. Statements were issued, targets were set, teams were established. Corporate websites began to resemble small manifestos about fairness, representation and opportunity.

None of this was entirely unreasonable. Businesses operate inside societies, and societies have been wrestling with these questions for a long time. But, as often happens when corporate enthusiasm meets social justice, the pendulum swung rather hard. I remember a period when DEI programmes multiplied rapidly and the language surrounding them intensified. Companies competed to demonstrate how committed they were to the cause. In some cases this then meant that initiatives became quite narrowly targeted – and occasionally clumsily implemented.

A recent article in the Harvard Business Review suggests that it wasn’t long after this, and in line with Trump’s second term being launched, that the lawyers started arriving. More than a hundred lawsuits have now been filed in the United States challenging corporate DEI programmes. Critics argue that some initiatives may themselves constitute discrimination, particularly when opportunities are reserved for specific groups.

Over the past year and a half, the tone has changed. Large American corporations have begun scaling back, rebranding or simply speaking less about DEI altogether. At the same time, it seems clear that a more conservative policy environment has taken hold in Washington and across parts of the Western world.

Does this mean the pendulum has swung back? I’m fairly confident that this latest pivot does not mean companies have decided diverse teams are a bad idea. Having spoken with various CEOs this year, many working in Asia, I’d say quite the opposite. Plenty of executives I’ve spoken with still recognise that organisations perform better when they can draw on a wide range of perspectives, experiences and skills. So, perhaps the problem was not the goal, but the packaging.

It often feels as though both the NGO and private sectors share a curious fetish for acronyms and jargon – one that tends to clutter the simple ideas sitting behind the labels. In my experience, what most organisations actually want is something much simpler. They want teams that work well together. They want leaders who understand different perspectives. And they want workplace cultures where people feel able to contribute.

These are not especially radical concepts. In fact, they have been the basic ingredients of effective organisations for about as long as organisations have existed.

Which brings me back to Asia.

I’d posit that the pendulum swing here has been far less dramatic than in the West. One reason may simply be that the region has approached the topic with a little more pragmatism. In many Asian workplaces, diversity is not something that needs to be invented or theorised about – it is simply the daily reality of operating across languages, religions, ethnicities and generations. That tends to shift the conversation away from ideology and toward something far more practical, namely to help people collaborate effectively despite those differences.

While some large companies operating in the region have adopted DEI frameworks, the conversation has generally been more pragmatic and considerably less theatrical. Which, in turn, might be a fortunate position for them to be in now because, as the Western corporate world recalibrates its language and tone, I think Asian organisations will find themselves slightly ahead of the curve. Rather than importing culture wars from elsewhere, companies here can focus on how they build strong teams in complex, diverse workplaces. The task is not to invent diversity, but simply to manage it well.

Optimistically, the next chapter of this conversation may look straightforward, and devoid of quite so much ideological framing. Instead, placing more emphasis on leadership, collaboration and culture. And if organisations find themselves needing a little guidance navigating this gently rebalanced pendulum, well, there are the occasional small consultancies out there ready to help.

Take mine – Coracle Consulting – for example. We spend a surprising amount of time helping organisations think about precisely these questions: how teams work, how leaders lead, and how workplace cultures evolve. No acronyms required.

The pendulum will keep swinging. The trick, perhaps, is learning how to stay one step ahead of it.