I remember the moment I started really thinking about inequality. I was 22 years old and part way through a year of teaching in Uganda. As cliched as that year has the potential to be (for the privileged expat that I am) and as eye-glazingly pathetic as this anecdote might come across, I’ve thought it through a fair few times over the two decades since, and it was out there, halfway down the main orange dustbowl of a road outside of the room I rented behind a local bar, that things changed for me.

It took only one minute – and it will forever raise the hairs on my arms.

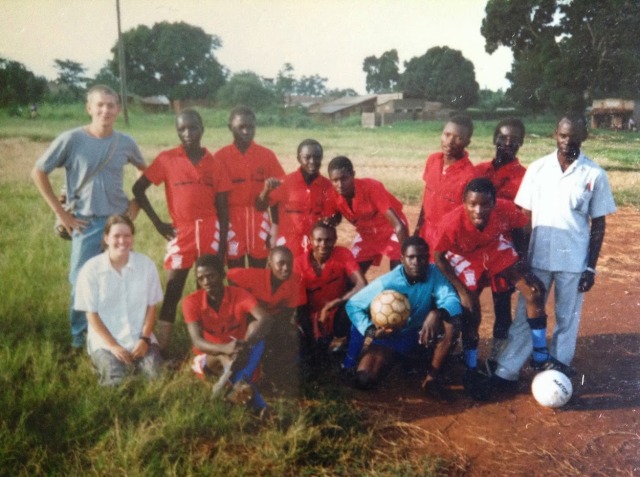

It was Sunday, and I was walking into the local town – Kiboga – with Julius, the headmaster of one of the schools at which I was employed as an English (and football!) teacher.

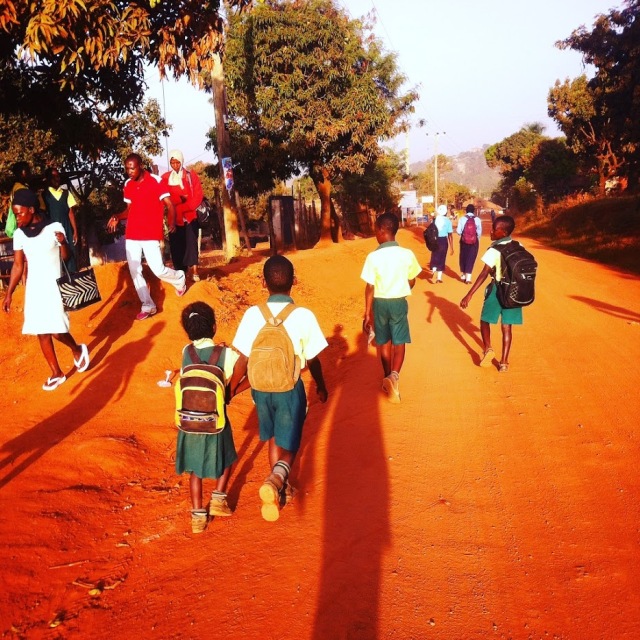

As was customary, a walk into Kiboga, on any given day, would involve multiple greeting stops, and smiles and gestures to my neighbours. Students on bicycles might swing past me shouting “yes, Master!” or a group of half dressed toddlers would canter several metres towards me from out of their houses yelling “Mazungu! Mazungu! how are you Mazungu?”

Julius and I had paused to talk to a man walking in the other direction to us, carrying what looked like a cardboard shoe-box. I didn’t get to meet him, Julius took the conversation on himself, mumbled and curt and, within thirty seconds, we were on the move again. I glanced behind me to take another look, as the man and his box shifted further on down the road, when Julius explained “he is burying his baby daughter,” and, without looking over at me he continued, “she died this morning.”

I don’t remember saying anything much after that, until we reached town and lost ourselves in whatever errand we’d been on in the first place.

The frailty and cruelty of that man’s reality was at best heart breaking and yet, the part that kept getting caught in my throat, and in my heart and in the pit of my stomach, was the very mundane and matter-of-fact ness of Julius’ report out on the tragedy.

Uganda, at that time, was enjoying relative peace. There were conflicts in the north, and reports of kidnappings not far from Kiboga over in the Rwenzori Mountains but, by and large, President Museveni, who’d been in power for some time, was continuing to oversee a country recovering well from the horrors of the Amin and Obote regimes.

And yet.

And yet, time and again during the years after I returned from Uganda to London – setting out on a initially quite meandering job pilgrimage, navigating through the private sector, the civil service and then a brace of UK charities, before finally landing a role with CARE UK in September 2006, along with a warming realization that this was where I wanted to stay – time and again, I imagined the folded arms and legs of that man’s daughter, neatly nestled inside her makeshift coffin.

Perhaps, if I’d actually seen her, the image would be less haunting. Maybe the sheer guilt of all I have to be thankful for in my life continues to torment me through the sustained fascination I’ve kept about her, and for what her short lived life might stand and count a generation later. She would have turned 21 this year.

In all the writing I’ve scattered over these pages it occurs to me that each post I attempt – like some fanatical pilot intent on making the pitch perfect touchdown, gently lining up the landing strip and deftly easing the wheels onto the tarmac in silent and smoke free respect – each post is designed to invoke thought. Thought from me, and from my reader.

If only we all thought in the same way about each other, and we all felt full of desire not for the now, or for the indulgence once more of the self, but instead that we re-directed the natural fuel and intention of our feelings elsewhere. To those closest to us, yes. But, beyond that, to those we meet each day on the street, in the park, on our travels.

These are what many of my blog posts seem to be trying to hope for. I’m sure many of them skirt this topic, concluding all too often (for them to really have any originality at all) that love and tolerance and understanding are the only lynchpins worth fighting for in life.

Out of guilt, or frustration or simple fascination with things I experience (more so than ever before since working for CARE) I’m nowhere near to articulating any of this any better than when I first set out.

If only, as usual, to find solace in some kind of summary (not quite landing the plane but dealing with the headwind, perhaps and at least) it seems to me, clearer than ever, that connection is all that we really have in life that comes to us for free, and which has the agility and a striking kernel of gravitas, to address some of life’s deepest anthropological and philosophical lines of enquiry.

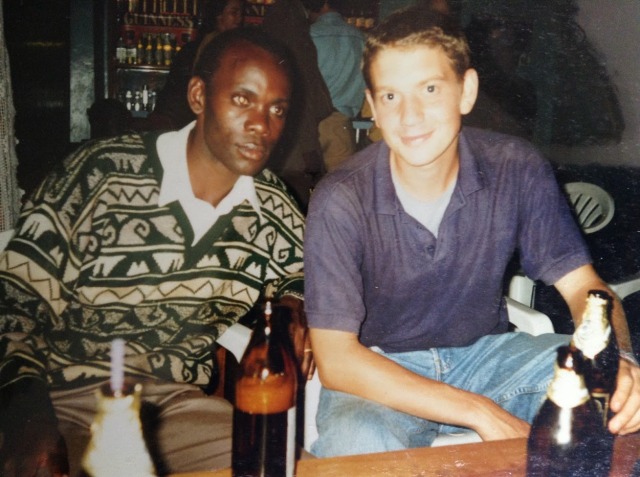

In Kiboga, for I’ve returned several times since 1997, there are, of course, disagreements and arguments and strife amongst the town’s inhabitants. Not a lot of the infrastructure seems to have changed all that much (something I noted when I last visited) and life felt much the same two years ago when I stayed with an old friend of mine, Michael (pictured.) Mobile phones and wifi are the main new additions to when I lived there from 1996-1997, but many other facets of life remain constant.

However, as Uganda and other countries on the continent, combat centuries of resource cursed transactions with pillaging nations (my own country sat fat at the top of that list) it does sometimes seem to me that my Kibogan friends have such an acute sense of connection, and of understanding about some of the pervasive issues that the likes of CARE grapple with from the cosy confines of our HQ offices, that we must ensure our continued work with local communities around the world finds the right balance of intervention at all times.

By which I mean – and this is to borrow the words of Ayanna Pressley when she said that “those closest to the pain need to be closest to the power, and inform public policy“.

This is a mantra my team at CARE have adopted recently. I like it. I’m mindful, too, that in adopting it, we still have a long way to go when it comes to finding appropriate means to provide “help” to others who are experiencing injustice.

The needs and the answers to how to resolve inequity in the world lie, this mantra would suggest, in the experience of those living out these unequal daily dynamics, each and every day.

In exploiting Africa’s minerals and profiting from the proceeds, we cannot now do the same in mercilessly extracting the very knowledge that resides in the hearts and minds of people who, this morning, might themselves be burying a young child in a cardboard box.

Many of us in the world – overwhelmed and socially impotent under the weight of materialistic distraction and click-baited detritus – seek out the type of connectivity and resilience that can be found sweetly fermented in the day-to-day culture and interactions of local communities around the globe. Conversely, many of these local communities dream for the type of economic gains that others continue to take for granted.

In balancing, ultimately, any relationship that an entity such as CARE might have with those we are seeking to lift up, our intentions to bring about change often fall short. Building trust through connection remains one of our best hopes, but that still requires nuance and thought and the art of listening.

If ever a starker reminder of how many local communities around the world today remain closed to the “Western” world’s humanitarian interventions, the incident this week of the man killed trying to visit India’s Andaman Islands takes some beating. In so comprehensively preserving the islanders’ eco-system and ways of life, the refrain of their message to the world around them, in acting as they did, is a powerful one.

******************************************

My musings will likely repeat and roll on for some time yet.

Exquisite and maddening truths uncovered, whilst an insatiable thirst for reason unfolds over and again.

The hairs on my arm, the tingle in my belly – those sixty seconds with Julius and the girl in the cardboard box, frozen in time.

A very moving and emotional piece. Brave of you to share. POPS

Thanks Pops and for being a loyal reader since 2011! Now and again a good story of self is required. Get it down whilst you can, I say 😉 see you soon X