Just been reading that Elon Musk is stepping down from his role at DOGE, the government department set up to save the US economy from wasted spending.

I’ve briefly shared my view on DOGE and on Trump, and I mentally flit between one day wanting to write more about how both entities are impacting the world (negatively, in my opinion) and the next day simply wanting the whole circus that is the US Republican administration to fall off the face of the earth.

If only there were some decent Democrat spokes-people out there, these past five months, to counteract the daily ordeal each of us faces when we read the news. Lucky enough I found this guy, Harry, to be a helpful and passionate critique of Musk and Trump.

There’s very little in this piece he posted recently with which I disagree.

The one thing I’d add to this latest piece “news” about Musk leaving DOGE is that, aside from the long list of grievances one would be well justified to level at Elon Musk (Harry covers this neatly, so I don’t need to), and aside from his general awkwardness with everyone he meets, and how he communicates, the thing that sticks most in my throat is his inability to collaborate.

His purchase of Twitter/X has only made his individualism and ego even more pronounced.

Forget the viability of something anymore (be it, say, the “truth” or simply the credentials of one’s EV business) many social media sites have together reframed what is important for society and that, it seems to me, is not viability, but visibility.

Misinformation thrives in these online spaces. Very complex ideas and hypotheses are flattened out into bulleted “top tips”. Twitter, in many ways, is a platform which has gamified shortened attention spans and praises individual’s visibility and their brand.

Which, of course, offers the perfect ground for performers like Trump and Musk, who pretend to be leaders, but act more like ham-fisted Copperfield illusionists. All accountability is removed. All sense evaporates as soon as they start speaking. They don’t answer questions, they gaslight, they lie, they rinse, they repeat.

While Musk claims to build for the future, with neural interfaces and colonies on Mars, he is a caricature of all the shitty habits and traits that we’re collectively adopting from spending too much time, ironically, scrolling through Twitter feeds.

It’s well documented that many people find it ever harder to hold their attention on simple tasks and activities. Young professionals, in particular, embrace more performative ambitions about what they want to do as individuals. It feels, a lot of the time, like there is a fading appetite for collective progress, as folks rush about in a melee of self-made busyness and unfinished projects.

As Musk bounces from city to city, flexing his enormous bank account in front of politicians one day and Silicon Valley the next, we watch as climate plans get drafted annually at COP Conferences, before being routinely shelved. We observe social justice campaigns that trend for days, before being eclipsed by celebrity gossip or some other geopolitical outrage.

Musk is a symbol for these contradictions. His own portfolio reflects a restlessness where the next ambition supersedes the existing one. Bored of this project now, move on.

Perhaps all of this is inevitable, given the world’s richest man is able to sway the markets with a single tweet, and can basically say or do what he wants today, and then pay for the damage afterwards, knowing that tomorrow we’ll all have moved on to the next click-bait article.

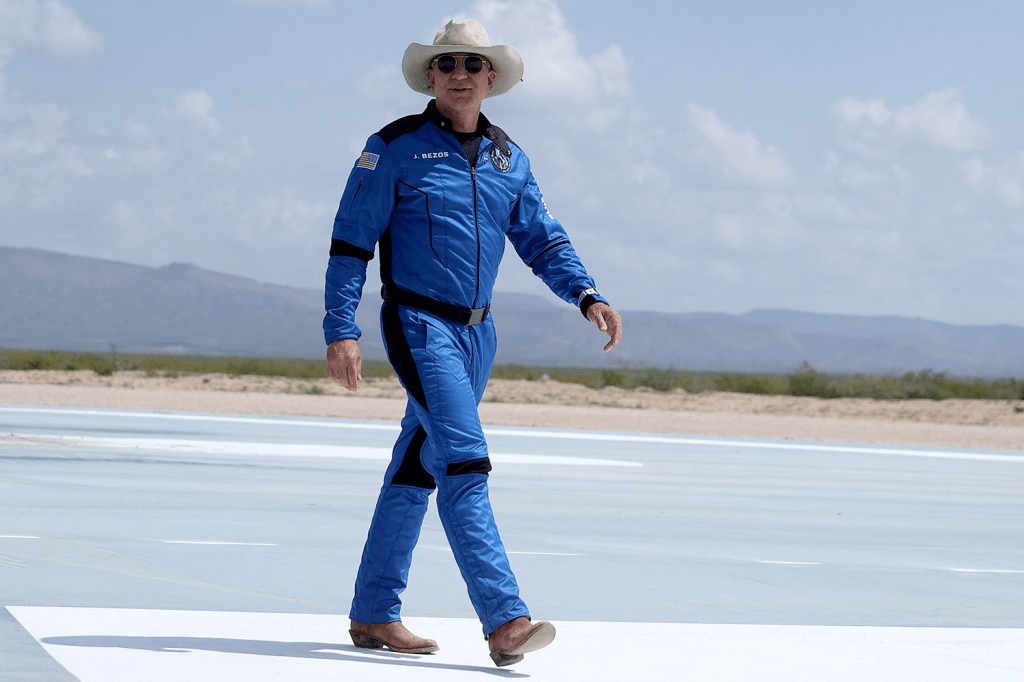

Musk is not alone, of course. As Jeff Bezos floated into Cannes earlier this month, in his $500m schooner, the irony was not lost on those who’ve followed his outspoken support to address climate change. And let’s not forget his Blue Origin space flight debacle. No, let’s.

Whichever of these wealthy elite you handpick for analysis, you’ll find the same paradoxes. The allure of the solo operator, at this echelon of society, remains powerful, there’s no doubt about that, and especially in a world that feels increasingly ungovernable. But the actions and behaviors of these individuals, forging ahead, indifferent to consensus, and chucking U-turns on a weekly basis, smacks of ending up brazenly erasing the work of thousands of others.

And, this approach fundamentally ignores the necessity of institutions, of partnerships, and the wholesome bindings of community. All of which are needed if we’re to arrive at long term solutions to global problems. We don’t need Musk or Bezos to do that.

You can tell me that Musk is responsible for cutting edge technological breakthroughs but, even if I choose to believe that, the nature in which he is conducting himself does not sit well with me, nor fill me with anything other than fear.

Musk, Bezos, Trump: these characters are in the headlines all the time, and they dominate how we think about change because of that. That’s a red flag.

Change that the world urgently requires is slow and deeply collective. We need sustained cooperation, and instead we run the risk of remaining stuck in a loop of promising beginnings and spectacular distractions.