I’ve been remiss posting on DefinitelyMaybe, having thrown my efforts into a weekly Substack instead – a decision that has yet to yield fame, fortune, or even a single sponsorship from a running shoe company.

In the meantime, no one’s mentioned my absence here, which I choose to interpret as proof that after twelve years of waffle I’ve covered everything there is to cover in the world of development.

Sadly for you, reader, I have not even scraped the surface of our sector’s bleak, lunar landscape.

It’s been an odd year, working freelance in development and humanitarian affairs. One of my last rants here was about Elon Musk’s DODGE experiment, following Trump’s cheerful levelling of USAID’s $40 billion portfolio. I can’t bring myself to post a photo of either man this morning – Musk currently awaiting a trillion-dollar stock decision, Trump berating New York’s newly elected Mayor, Zohran Mamdani.

Today, I want to talk about the future of job applications.

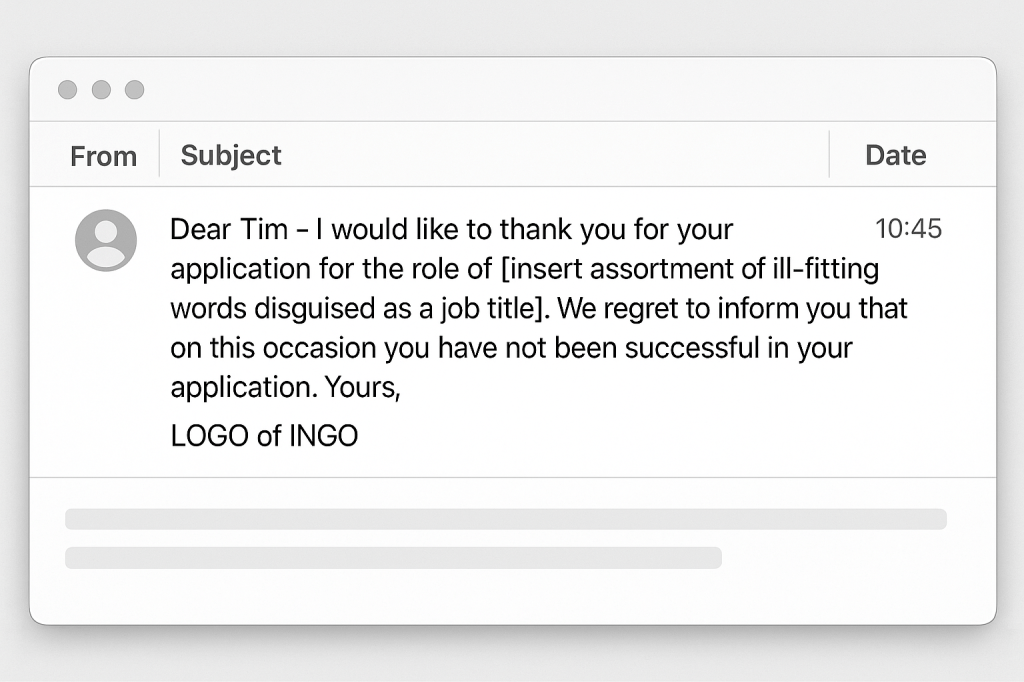

The email above is verbatim from an INGO that rejected me for a “Head of” position. I get emails like these a lot and am comfortable sharing that. It was a rather whimsical application to be fair, given the last six years I’ve been in the market for short term consultancies rather than full-time roles.

However, even with my freelancing I’ve probably only struck gold three times, after spending hours crafting pitches to advertised assignments. Ironically, the most lucrative of those was also the most haphazard application I submitted – a lesson in randomness, if ever there was one.

Most of my consultancy work comes through word of mouth. For that, I’m sincerely grateful. I intend to keep going, not least because my track record with formal applications suggests remaining solo may be wise.

It makes me wonder: is there really no better way for organisations to find people than the tired ritual of CVs and cover letters?

I write this, of course, while still mildly irked by that latest “thanks, but no thanks” email above – copied and pasted as it so often is in the first person, yet unsigned at the end, it felt like a passive-aggressive ghost of correspondence, glaring at me in my in-box.

As this isn’t the first, nor the last, rejection I’ll receive, I did want to share some of the inadequacies I see in the overall recruiting paradigm we have to wade through in the development sector.

Standing Out in the Crowd

Firstly, and as usual, I have no idea what part of my application failed the test, based on the email sent. Was it tone? Experience? Am I too old? Too informal? Should I have omitted my perfectly reasonable demand for sixty days of annual leave and a 25% pay rise each year?

Certainly one can ask for feedback, but some rejection emails even come with disclosures like this other one I received:

“Due to the number of applications received and reviewed, I am not able to give individual feedback at this time, though I do encourage you to consider and apply for one of our consultancy opportunities in future.”

Recruiters tell me the challenge now is volume. Every LinkedIn posting draws hundreds of applicants within hours. Many are AI-generated, indistinguishable from spam. In that flood, it’s little wonder HR teams can’t respond personally. The process has become automated compassion. Efficient, yet entirely devoid of empathy.

And sometimes the role was never really open at all. The ad is window-dressing for an internal appointment already made before your polite rejection hits your inbox. Everyone knows this game.

The Human Touch

When I was recruiting for CARE in London twenty years ago, the process felt clunky, but sincere. Applications came by post, HR filtered the pile, and you spent a weekend reading twenty or thirty of them, scoring each against the criteria. You’d imagine who these people might be, wonder how they’d fit, and inevitably be surprised when you met them.

“He’s nothing like I thought he would be,” we’d gush after the first interview, perhaps a tad disappointed. Then the second candidate would arrive, and we’d instantly revise our judgment of the first.

I want to be careful here, harking back to these times and to any over-reliance on the in-person interview. There’s a strong argument that you’d be just as well to flip a coin, rather than judge two candidates battling it out in 45-minute interviews. I’ve seen plenty of people ace their interview but then turn out to be terrible at their jobs – and vice versa.

That said, while my old team’s deliberations about candidates could be chaotic and subjective, at the same time they were undeniably human deliberations. We’d agree, disagree, wind each other up, have a laugh about it all, and then take a punt on someone. It was a messy chemistry of people trying to imagine other people in their world.

While an interview is only one piece of the puzzle, I hope these deliberations still play out in some teams because it feels instead now that many just outsource that time and imagination to algorithms. Which results in extra pressure on candidates to hit the right keywords, and on recruiters to do the same with the right filters. I think the combination of which can mean people, at times, feel unseen.

Technology was meant to create fairer hiring practices, however I’d argue some of the stuff that used to make it feel more real – the chance for surprise, or for discovery, or for seeing someone as more than a list of verbs and achievements – has been lost as a result.

In Trust We Trust

Truly one of the best litmus tests for success here is trust. Someone who’s seen you work, who believes in you, or introduces you to someone else – that format can work really well, and is devoid of an algorithm and a cover letter. This way of doing things is also, clearly, not comprehensive enough of a format on its own to work for everyone.

There likely isn’t one silver bullet that comes close to solving the dilemma of how to best fill all the roles out there, and all the needs. We will have to use the internet to advertise. I just think our systems for doing so have taken out some of the vital aspects of what used to be there. CVs written by ChatGPT, and rejections by chatbots – where do we go from here?

Perhaps the future of hiring is more about a ten-minute audio pitch instead of a cover letter? Have any organisations out there experimented with short paid trials? Or could claim they host interviews where candidates ask as many questions as they do as recruiters? I’d love to hear from anyone on this.

For me, anything that reintroduces more elements of curiosity, risk and humanity into the exchange would be refreshing.