Those of you familiar with my writing will know I love the chance to hat-tip an anniversary.

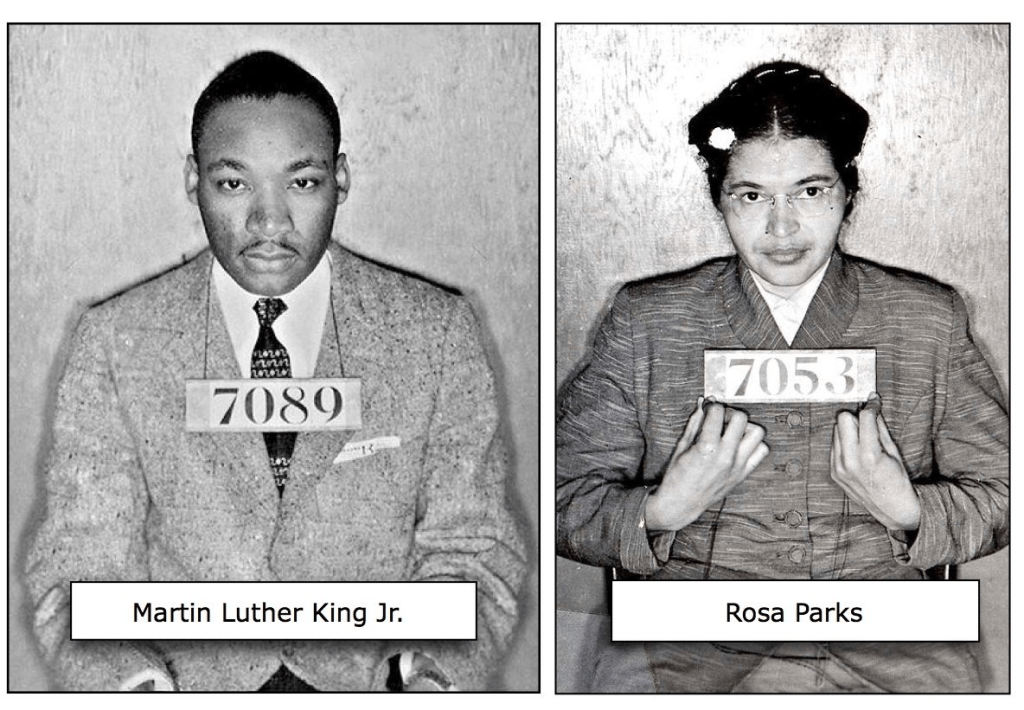

As well as today being the first day of the last month of the year, it is also 70 years to the day since Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama – and was arrested for it.

Back in 2018, I spent time in the United States for work, travelling through the South, visiting museums, memorials, and sites of the Civil Rights Movement. It was one of the most affecting trips of my life.

I wrote about it at the time, and re-reading that text over the weekend reminded me how fortunate I was, back then, to have a job that enabled me to make that trip in the first place.

It dawned on me too that, since leaving CARE International in late 2019, some of my focus has – perhaps inadvertently – shifted.

While with CARE, I was afforded daily access to issues of social rights, well-being, injustice, gender inequity – a myriad of interwoven concerns that constantly reminded me of my own privileges.

Since becoming a freelancer, it feels like I’ve turned much more inward: to the work at hand, to the immediate need to secure the next contract, the next rent payment. And this has often been at the expense of expanding my understanding of those deeper issues I knew so well, only a few years ago.

On that 2018 excursion I met some incredible people – one of whose work was introduced to us when we visited the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, which he founded. His name is Bryan Stevenson, and he’s an American lawyer and social-justice activist, who has spent decades challenging racial bias in the criminal-justice system.

In his book Just Mercy, Stevenson writes about the many hundreds of young Black men he has defended. I remember his staff showing us around the Institute, and wearing T-shirts with a quote from Stevenson emblazoned on the back:

The opposite of poverty isn’t wealth. The opposite of poverty is justice.

When Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat that day in 1955, she lit a fuse for a year long boycott that ultimately overturned segregation on public transport in Montgomery.

Her defiance is remembered as iconic. Hers, like Luther King’s, was a moment that changed history.

Rosa Parks’s story and legacy suggests to me that bringing about change is rarely born from comfort. It comes instead from friction, from disruption, from relentless organizing. Sometimes, as in her case, from all of the above combined.

Revisiting this, I’ve read more about how, at the time, many mainstream newspapers and officials framed Rosa Parks as tired, weak, and elderly: a harmless “grandmother figure” whose feet simply hurt.

That narrative was constructed deliberately to make her protest easier for the wider public to digest. In doing so, the narrative then became easier to sanitize, and easier to depoliticize.

But the truth is more powerful. Rosa Parks was 42 years old – not frail or dithering. And, as she later said:

The only tired I was, was tired of giving in.

Long before that bus ride she was already a seasoned activist. She was trained in non-violent resistance, she was connected to organizers, and she was committed to racial justice.

By 1955 she had been deeply involved in civil-rights work and had supported earlier landmark cases of injustice – including the defense of the Scottsboro Boys, a group of nine Black teenagers wrongfully accused of rape in 1931.

Their rushed trials at the time – complete with all-white juries – and their near-execution, exposed the brutal racial injustice of the legal system, and very likely shaped Parks’s understanding of what it meant to fight for justice.

Her refusal on that bus was not a spontaneous act born of fatigue. It was a strategic, courageous choice by someone who understood exactly what was at stake – as well as how much work still remained.

I don’t know how much Rosa Parks, or any of her peers at the time, believed there was an alternative route to justice than the one they took. What seems more truthful is that their actions were born out of necessity and fierce conviction. They acted not because it was safe, or convenient, but because it was right.

Today, at the beginning of the end of another year, I’m struck by how easy it is, in our everyday lives, to drift toward comfort. We focus on earning, and planning, and surviving – this is what we do, these are the things we use for structure, and for our milestones.

And, while I don’t see how to get around some of these inevitably important components in one’s life, I do wish personally I’d spent more time of late listening and learning from those others out there, who have leant hard into the practice of intentional solidarity.

I’ve found myself proactively turning away from reading more about some of the ongoing turbulence in the world. And in doing so, missed opportunities to be inspired by all the many other “Rosa Parks figures” in the world: individuals, often far away from our lives, bravely doing things differently, guided by resolve, endurance, and principle.

One of them is Malala Yousafzai. Even now – years after surviving a brutal attempt on her life, and years after winning the Nobel Peace Prize – she continues to remind the world why education is not a privilege, but a right. When I first learnt about her story she immediately inspired me to write about some of the issues she stood up for.

Looking her up now, it’s thrilling to read that through her ‘Malala Fund’ she continues to supports girls, particularly those in conflict zones or under oppressive regimes. She is helping them complete their secondary schooling, stand up for their rights, and ultimately claim the futures that too often are denied to them.

Although she has repeatedly spoken out about the dire situation facing Afghan girls, this year she went to Tanzania to convene activists around a range of similar issues – from girls’ education and child marriage to digital inclusion and climate justice.

To me, Malala is another history changing icon. In some ways, she stands as a bridge between the legacy of 1950s civil-rights movements and the contemporary realities that my work with CARE also brought to life for me: global inequality, gender injustice, and the woeful disenfranchisement of entire generations of girls.

I’m very grateful for the chance to regurgitate some of the lessons I took from that US trip seven years ago, and to commit more in my life to reach beyond convenience, to pause, to read, and to listen much more to voices I don’t normally hear.

Just because we’ve got used to the media peppering us with images and stories of characters who couldn’t behave LESS like those I’ve written about here today, it doesn’t mean we have to take any lead from them, or from what they represent. If, instead, we have to go back in time to find better role models and more worthy solutions to social inequalities, then so be it.

Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr., Malala Yousafzai: these should be the trend-setters of today, the influencers in our lives.

I will always applaud them, and all the many others out there like them – people who refuse to accept easy comfort, when it comes at the cost of justice.

You must never be fearful about what you are doing when it is right.

Rosa Parks (Feb 4, 1913 – Oct 24, 2005).