I’ve been listening to The Rest Is History lately and, in particular, snippets from various episodes discussing the First World War.

Aside from the irony that it’s taken me thirty-two years since leaving school – and leaving behind two underwhelming history teachers in my wake – to finally get to grips with how WWI was staged, is not lost on me.

During the late nineties, the first time I encountered Franz Ferdinand was on the dancefloor of nightclubs around Clapham Junction, assuming they were simply a catchy, alliteratively named band who knew how to bang out a chord. I’m now suspecting their infamous chart-topper Take Me Out was penned with tongues firmly in cheeks (by their own admission they chose the name because it sounded like something that could “blow up the world.”)

In any case, there are two takeaways that stuck with me while listening to the podcast.

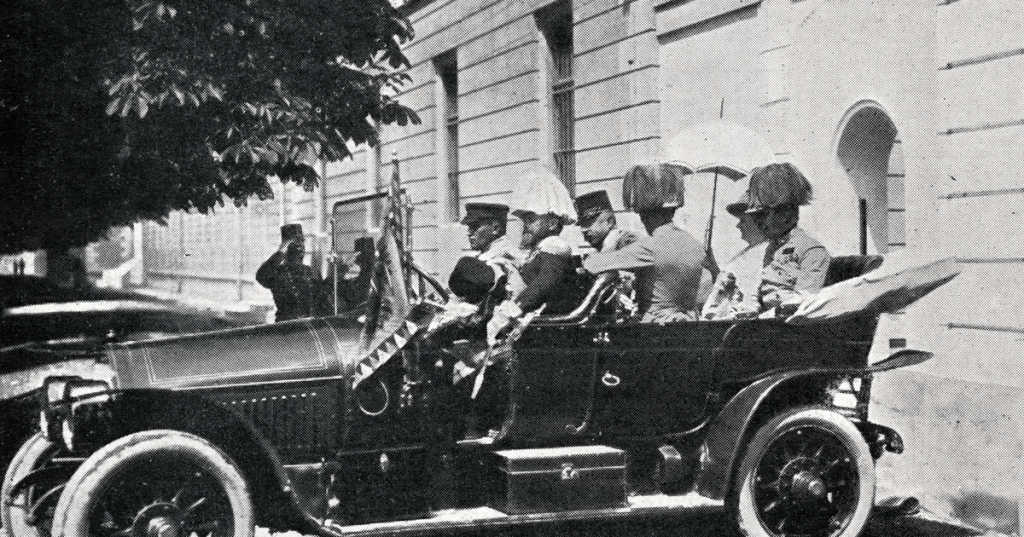

The first being that, if ever there was a story that presses home the old adage that “the flap of a butterfly’s wings can cause a hurricane,” it is the assassination in Sarajevo of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, on 28 June 1914.

What began as a botched plot – a missed bomb, a wrong turn, a paused car – ended with two gunshots fired almost by accident on a street corner.

As the podcast hosts infer, Ferdinand was not even the most enthusiastic standard-bearer of empire, nor a particularly popular figure at court, yet his death proved enough to unpick a continent. Within weeks, Europe was at war.

The First World War did not erupt solely because of one man’s death, of course, but without it the fuse might have burned far more slowly – or fizzled out altogether.

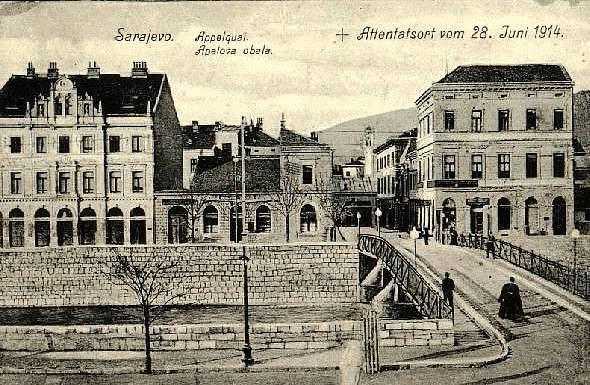

Sarajevo (also, up until now, a place about which I had very little intel) was a charged stage for such a moment to play out. It sat at the fault line of empires, religions, and identities. Austria-Hungary controlled Bosnia at the time, a symbol of occupation to many Slavic nationalists. The Archduke’s visit on 28 June was seen by some as provocation, by others as opportunity.

That the world’s twentieth-century catastrophe should hinge on a wrong turn beside the Miljacka River feels bizarre in its randomness.

And yet, listening to the story unravel while weaving through Saigon’s morning markets, it struck me how often history turns not on grand designs, but on small misjudgements and human impatience.

My second takeaway came via Stefan Zweig, also discussed and quoted on the podcast. Writing years later, with what can only be described as bitter clarity, Zweig reflected on how war momentarily dissolves the smallness of individual lives. He described people being “drawn into world history,” purified, if only briefly, “of all selfishness” – their private anxieties submerged beneath a sense of collective fate and shared urgency.

That sentiment stayed with me, perhaps because it is both unsettling and persuasive.

I’ve read before about the apparent inevitability of conflict and, awful as it is, history suggests it has been one of the few forces powerful enough to collapse social divisions and align purpose. In doing so, it can be a reminder for people that they belong to something larger than themselves.

As conflicts around the world continue to grind on today, it seems we’re still not ready to invest in ways of creating that same level of solidarity – one I suspect most people would willingly sign up to – without first tearing something, or someone else, apart.

I finished the episode, and stepped back out of the Saigon heat, and I felt that thing (that I suspect I was supposed to feel back in the classroom when I wasn’t paying attention to my history teacher) where it’s so damn obvious that history is not some distant, sepia-toned abstraction, but something that unfolds in ordinary places, on ordinary mornings, through choices that feel inconsequential but which prove to be quite the opposite.

For a while now, commentators have been writing about history repeating itself. That is a chilling prospect, made more so by the idea that it so often feels familiar while it’s happening.

The hurricane always needs its butterfly. The unanswered question is whether we’ll ever learn to flap our wings more deliberately.